You’ve heard this story before. You know what happened to the people on that train.

It's November 5, 1942, three years into the Second World War. After a harrowing four years on the run, this is the day a 21-year- old named Leo Bretholz would be loaded into a cramped cattle car — the newest member of a precious load of humanity being deported from France towards Auschwitz.

But Leo is an exception — he never made it to Auschwitz.

Just hours before reaching the German border, Leo and his friend Manfred used their sweaters and their unwavering will to live to pry apart the bars on a small window and leap from that moving train into the night.

But, this is not the feat Leo would become best known for. That happens in the final years of Leo’s life — almost 70 years after his escape and subsequent immigration to Baltimore, Maryland.

SNCF, France’s national, state-owned railway, transported 76,000 Jews and thousands of others (including U.S. pilots shot down over France) toward concentration camps throughout Europe. They were paid per head and per kilometer for those who they deported during the war.

Leo and other survivors had advocated unsuccessfully for the French to pay reparations for their role in the genocide. Then, in 2009, SNCF began pursuing lucrative high speed rail and commuter rail across the United States — including in Leo’s home state of Maryland - and everything would begin to change.

Leo, now flanked by a pro bono legal team and a group of survivors, saw his chance.

It would be untenable for the French to deny the role their trains played in such atrocities and at the same time lay tracks through states where so many survivors later found refuge, and ask for these survivors’ tax dollars no less. The French simply couldn’t have it both ways.

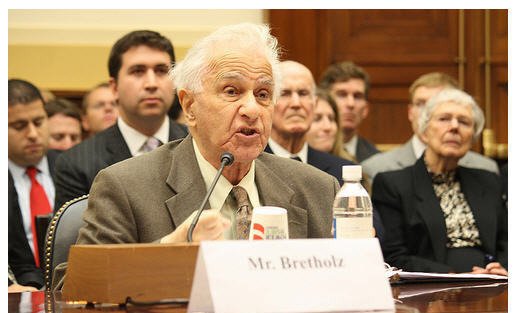

Leo went from a French cattle car bound for certain death to the treaty room of the U.S. State Department — he relentless worked along the way to convience everyone that these victims deserved a sincere expression of contrition and accountability from the oldest ally of the United States.

This campaign for justice, unfolding on a three dimensional chessboard, was waged in the courtroom, in state legislatures throughout the country, in the halls of Congress, in the highest level diplomatic negotiations, in corporate boardrooms, and in the court of public opinion.

Ultimately, the United States and France negotiated an unprecedented settlement.

France paid more than $60 million to survivors and descendants of the people transported by SNCF toward the death camps. While no settlement could ever fully address these atrocities, it was an unprecedented and improbable settlement with the United States’ oldest ally, and ultimately helped pave the way for President Macron to deliver France’s most public and fulsome acknowledgement of the role it played in the Holocaust.

This global campaign raised important questions about justice and how to provide accountability to the victims — monetarily or otherwise — for their suffering. It brought together historians, survivors, descendants, CEOs, and politicians of the highest level to unpack the question: how does a corporation or a country say it is sorry?